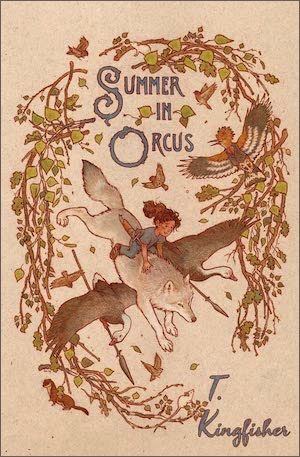

Thanks to commenter BrendaA for recommending T. Kingfisher’s novel as a followup to Stephanie Burgis’ Dragon Heart series. It’s perfect. Kingfisher, an open pseudonym for author Ursula Vernon, notes in her afterword that this is a bits-and-pieces project. It’s all the little bits she’s thought of over the years, sewn together into a quilt that owes a strong and explicit debt to Narnia, but goes off a direction that’s completely its own.

Summer is eleven years old. Her mother is pathologically overprotective; Summer is not allowed to do much of anything, because everything might be dangerous. She copes as well as she can, but the longer it goes on, the more determined she is to escape.

Then one day a house walks into the alley behind the back garden. Summer is locked into the garden, but that doesn’t stop her from discovering that the house walks on huge chicken feet, and that the old woman who lives in it is none other than Baba Yaga. Summer’s mother’s padlock is no match for Baba Yaga’s magic. And Summer has found the escape she’s been dreaming of.

The witch is in a good mood, which is a good thing; when she’s in a bad one, she eats people. She offers Summer an adventure, a quest to find her heart’s desire. Summer isn’t at all sure what that is, though she’s thinking she’d like be a shapeshifter.

Maybe. It could be a bad idea. Summer likes to think things through. She does it early and often, and she does it thoroughly.

Baba Yaga sends Summer to a pocket universe a little like Narnia, with a talking weasel for company, and a set of somewhat cryptic instructions. The portal is a long corridor lined with magical stained glass, and the world it leads to is called Orcus. Orcus is as American as Narnia is British; it’s full of talking animals and talking birds, and large parts of it bear a striking resemblance to the American Southwest.

I live in that country, and I love that this book celebrates it. The stony landscape, the scrubby trees, the giant columnar cacti—that’s the fantasy world I walk in every day. The creatures who populate Orcus are numerous and varied, from flocks of mid-Victorian-esque birds in waistcoats and cravats to hideous horse-spider hybrids to the weird and complicated creature that is the Antelope Woman.

And, of course, shapeshifters. Orcus is full of them. As commenter BrendaA mentioned in the previous post, there’s a dragon transformed into a human. The nature of her transformation isn’t quite like any I’ve seen before. It’s not so much a metamorphosis as an exchange. A human girl wanted desperately to be a dragon. She took the dragon’s shape, and the dragon was forced into hers. Both of them kept their essential nature, but the dragon was squeezed down and down into the form of a small girl, and the small girl’s mind and energy were lost inside the body of an enormous predator.

The dragon makes the best of it, and becomes the wise guardian of a realm in Orcus. The girl suffers terribly for what she’s done. Hers is, truly, a fate worse than death.

Other transformations are less harrowing, and some are delightful. The three skin-changers, Bear and Boar and Donkey, have sorrow in their past, but they do well enough in the present, and they help Summer with her quest. Best of all is the wolf whose name is Glorious.

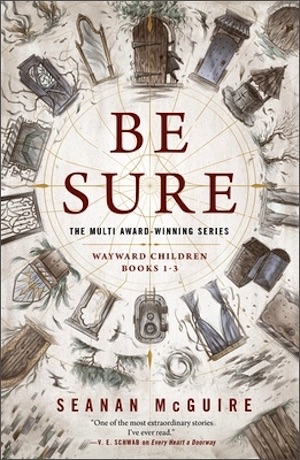

Buy the Book

Be Sure

He has fallen prey to a shifter curse. Every night he transforms into something else altogether, which leaves him helpless until morning. But he makes do. In the daytime he’s one of Summer’s best and strongest allies. At night he shelters and protects her and her friends.

Wolves, Kingfisher tells us, are remarkably susceptible to transformation spells. She doesn’t say it in so many words, but I couldn’t help but think of the plasticity of puppies. It’s a remarkable thing about the dogs who descend from wolves, that their genome is so flexible; that they can come in so many different sizes and shapes. It’s no wonder werewolves are so prevalent in lore and legend.

Glorious is lovely, but the dragon’s fate is a lesson in being careful what you wish for. Summer concludes that shape-shifting is not her heart’s desire. What that is, and how she finds it, is not anything that she expected. She’s not a hero, nor does she want to be, and she doesn’t want to save the world.

That’s what makes this book work. It doesn’t go in the usual directions, or follow the usual rules for fantasy adventures. Its villains range from dastardly to hideous, but they have their reasons. They make sense, in their way. Not all the people of all species who help Summer are good or mean well. Some who seem good turn out to be bad, but again, there are reasons for it.

This is a book that knows its genre really, really well. It’s got a solid grip on the rules and the tropes. When it bends them or complicates them, it knows exactly what it’s doing. It doesn’t offer any easy answers, and not every beloved character makes it through to the end. But that end is satisfying. It gives us the payoff we’ve hoped for.

Judith Tarr is a lifelong horse person. She supports her habit by writing works of fantasy and science fiction as well as historical novels, many of which have been published as ebooks. She’s written a primer for writers who want to write about horses: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. She lives near Tucson, Arizona with a herd of Lipizzans, a clowder of cats, and a blue-eyed dog.

This is on of my very favorite books of all time. I could not recommend it more highly. Thank you for bringing it to more people’s attention.

Everything Ursula Vernon writes, whether as her regular self, or as T. Kingfisher, is wonderful. I don’t read horror, or romance, but I read and love hers.

I’m very fond of this book. I love Glorious, and also Reginald the hoopoe, who is a fop in his cravat and waistcoat but makes a far more reliable traveling companion than he seems at first.

I fell totally in love with this book on first reading. The second reading actually hasn’t happened yet, but it will!

If you want the inverted, horror Narnia try The Hollow Places, written under her T. Kingfisher name.

I’m so happy to see this book getting attention! If you like the atmosphere of her desert descriptions, you should definitely read two of her short stories, “Jackalope Wives” and “The Tomato Thief” – they are amazing.

https://apex-magazine.com/short-fiction/jackalope-wives/

https://apex-magazine.com/short-fiction/the-tomato-thief/

This is one of my favorite books ever, and certainly has my favorite ending to a portal fantasy. It brings all my childhood favorite tropes home to roost, reminding me of why I got into reading in the first place. (It’s also free on the author’s website in its entirety.)

Delighted to hear about this book. Thanks!

I love this book as well! I love everything she has written, including her children’s books – the Dragonbreath series is the best! I try to promote her books at my library to kids and adults.

Oh, yes. I love this book so, so much.

I’m happy you had a chance to read it and enjoy it as much as I do. :-)

I made sure to get a hardbound copy of this and reread it every so often. It still really bugs me this wasn’t deemed appropriate for children; my inner child STILL needs books like this.

I’ve read a number of books by Vernon and Kingfisher, and I have to conclude that her approach to genre fiction is to run up to a genre, waggle her fingers in her ears and blow a raspberry, turn around and wave her tush at the genre, then grab the best stuff and run off, leaving the genre to wonder just what the heck that was all about.

omg! I loved Ursula’s Digger so much, and now this sounds wonderful too! On the hunt for a copy of my very own!